Rotterdam Mountain

The Mountain is a concept created by the Rotterdamse Dromers, to cover highway and railway intersections in the Netherlands. Each mountain creates a large amount of residential and commercial floor space as well as recreational area. Rather than form a barrier, it connects previously disjointed urban areas. Underneath, it combines distribution centres with the existing high- and railways, ideally situated to service the surrounding city, and avoiding the need to convert current rural areas such as farmland. Large data centres and other industrial functions are taken from view, while their waste heat is captured and converted to energy for the apartments, offices and hotels. Summum Engineering evaluated the possibility for the mountain surface, a cable network, to structurally connect and stabilize the towers, whilst reducing their exposure and transferring wind forces more efficiently to the ground instead. A parametric model allows rapid reconfiguration for different intersections and site conditions.

“Die berg komt er!” That mountain will get there! With those words, an initiative led by journalist and former cyclist Thijs Zonneveld was presented to the world in late 2011. Their plan, which proposed eight potential locations, comprised of a hollow mountain with various functions within. In addition, the mountain offered space for cycling enthusiasts to test their legs in the typically flat country of the Netherlands. There are different reasons why that mountain never got there. The main argument was the insufficient financial and technical feasibility of a 2 kilometer high mountain, situated in the Dutch countryside.

Thanks to an avid follower of the Rotterdamse Dromers (Rotterdam Dreamers), they reinvigorated this idea, albeit within a wholly different framework. Instead of replicating an Alp, the plan called for a much lower mountainous structure, covering infrastructure such that it no longer acted as a barrier but as a link within the Dutch landscape. By layering the mountain with various functions within, it becomes a solution to the current issue of ‘big boxification, threatening the cultural landscape.

Read the original article by the Dreamers in Dutch here.

Video

A real mountain doesn’t exist in the Netherlands. Hills or slopes are as good as it gets, in the smoothed out landscape. A building that looks and functions like a mountain on the outside does not exist anywhere in the world. The present concept was inspired by the traditional festival-tent that spans several pylons to cover any large number of party-goers underneath. The difference with this tent, is that Rotterdam can house large swaths of city underneath, while being strong enough to support people and nature. Ideal to span across stretches of unusable land and do away with barriers in a city. And to create space in the already densely populated country of the Netherlands, where arable land is being usurped by distribution and data centres.

Structural feasibility

An important question is the structural feasibility of the concept. A mountain consists of an enormous amount of soil, along with an unimaginable amount of weight, that the weak Dutch soil would have trouble carrying. In principle, the structure has to contain the lowest mass possible. The less downward pressure, the more mountain there could be. Preferably a thin layer of flora, covering the Terbregseplein intersection like a smart roof. Yet, thick and strong enough to carry soil and pedestrians. With locally some structures, trees or heavier functions, to make the mountain come a live. The objective is not to reach a height of 2 kilometers, like previous plans called for. As high as feasible is the goal. The reference of a strong tent comes close to what we are looking for, except size XXXL.

Body cells and tents as inspirations

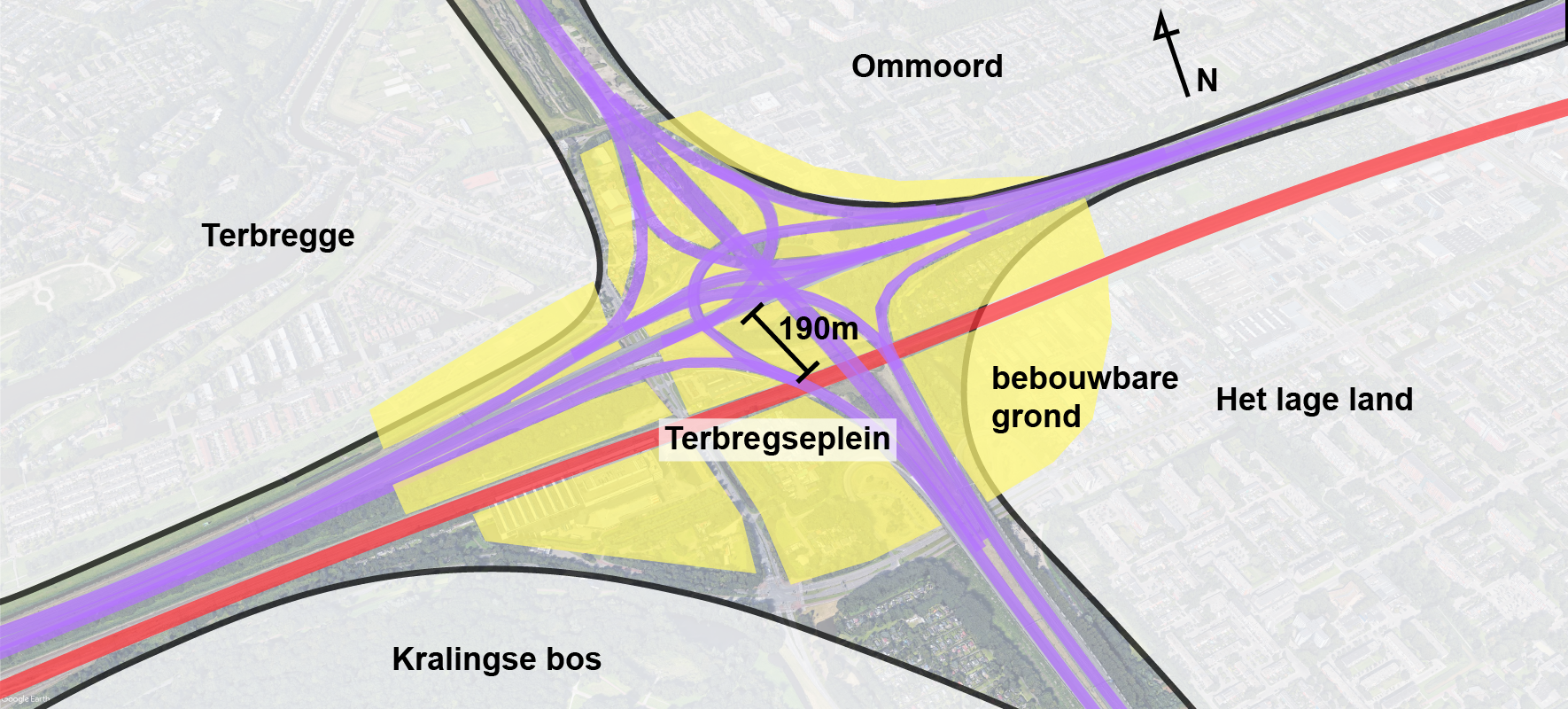

The challenge was to position the towers only on allowable space in the intersection. A parametric design model by Summum was used to ensure this condition, while equalizing their relative distances to distribute the mountain’s weight as evenly as possible. In effect, the towers are placed relative to one another like cells in a body, with the cells forming the basis for a structure of cables. By using a so-called ‘form-finding’ method, an optimal balance is struck between the desired prestress and mountain loads, resulting in a doubly curved shape. The towers are dimensioned based on the maximum allowed slenderness. The towers seemingly protrude through the mountain, but in fact are the pylons that hold it up. This produces a building that adds unprecedented amounts of space to the periphery of a the city, without claiming a gigantic footprint to do so.

High-rise versus guyed masts

The forces on the ground from a highrise, are not just it’s weight. More often, the worst combinations are governed by wind. A high-rise tower is usually constrained by a slenderness of 1 over 8, meaning its height is eight times the width of its base. An example is the Maastoren in Rotterdam, the tallest building in the Netherlands with 165 m height. The tallest structure however is the 372 m Gerbrandytoren, completed in 1961.

The reason for this greater height are the guys: large cables running to the ground, stabilizing the whole. Such a guyed tower can transfer wind loads to the ground more efficiently, and as a result is more slender. The most extreme example is the Dubai Creek Tower. It is expected to exceed 828 m – they are being a bit secretive about it – breaking the current record of the Burj Khalifa.

Skyscapers with guy-wires

A guyed highrise tower would combine the structural efficiency of the former with the functional potential of the latter. If the height and slenderness is more modestly chosen than in Dubai, those benefits could be converted into a more lightweight building design, a more transparent facade or more usable floor space.The Rotterdam Mountain consists of multiple such towers, but instead of connecting them to the ground, they stabilize one another.

Cables anchoring the mountain

The mountain surface is created from a network of cables. On top, there is a secondary structure with vegetation: grass around midspan, heavier shrubs around the towers, and trees on the rooftops of towers that are cut off at mountain level. For the largest spans, the weight is further reduces by domes of glass, polycarbonate or ETFE, that also double as deep light shaft, to allow daylight to enter below.

The prestressed, doubly curved network transfer the wind through so-called membrane forces: pure tension in the plane of its surface, without any bending.

The increase in vertical load on the towers, due to the prestress and weight of the mountain is equal to about three to four storeys. However, this additional load can be offset by reduced bending moments due to wind. The wind flows along the gentle slopes of the mountain surface, and cause lower pressure than it would have on the vertical tower facades. Underneath its surface, the towers are no longer subject to wind, meaning resulting bending is vastly reduced, especially at the base. As a consequence, no crude, monolithic mountain, but a lightweight structure with space for commercial functions, with conventional foundations for the towers.

Along the perimeter of the mountain, it is tied to the ground. With a tent, you would need ground anchors, or tent stakes – an expensive type of foundation. Instead, the Rotterdam Mountain exploits the presence of surrounding low-rise buildings. They act as ballast, also avoiding the need for any special type of foundation system. Along the cable-net, and over the green roofs of this low-rise, people can descend down to the adjacent neighborhoods of Rotterdam.

Mountains for all

A flexible, parametric setup allows for rapid redesign of the concept, depending on the geometry of each unique intersection. Perimeter, height, allowable space between existing rail- and highways, and the desired amount of towers can be entered into the model. The mountain is then regenerated based on the new spatial boundary and local soil conditions. In this manner, each intersection could feature a mountain. The spatial planning determines the shape of the mountain, so each city can customize its own mountains.

Recreation

A mountain is mostly associated with recreational functions. Hiking, cycling and skiing, while enjoying the fresh air and taking in the views. The Rotterdam Mountain can also accommodate these functions. With sixfold the level of current municipal ambition for green space, this finally connects the Kralingse Bos and Bergse Plas. Suitable for hiking, jogging and cycling. In wintertime, children can go sledding. The Kralingse Golf could realize 18 challenging holes on its hilly terrain, and an ambitious entrepreneur could even build a luge track. This would be the largest, greenest playground area of the Netherlands, with an appeal that crosses borders.

Residential needs

A site was chosen that is not being considered for residential purposes at all, the Terbregseplein intersection. Instead of a highway with exhaust fumes, railroads and industrial areas, the Rotterdam resident would gain a completely new landscape with thousands of apartments. In this way, infrastructure would no longer form a boundary between the eastern parts of the city, but would form a contiguous urban area thanks to the Rotterdam Mountain.

The size of the complex has a magnitude that allows for a number of residences equal to that of downtown Rotterdam. The one million additional households that the Netherlands will have by 2030, could be positioned close to the city with this approach of converting existing intersections. All this without sacrificing any rural ‘polder’ area.

Big-boxification and data centers

Large windowless boxes in the countryside quench the constantly growing thirst for data and packages. The mega-barns currently under construction and in planning stages alone would consume 2 million square meters of valuable land. Instead, within the belly of the mountain, space for logistics is reserved. It already contains roads and railways that logistical companies are eager to connect to. Outside of view, but in the heart of the city and with a direct connection to high- and railway. No truck or train has to enter the city. Transferring cargo and carrying on, without causing noise or smell complaints. Residents of the mountain can pick up their packages by simply taking an elevator, while bicycle delivery takes care of the last mile for everyone else. In addition, the mountain forms Rotterdam’s very own high-tech datahub, meeting its inhabitants’ and companies’ voracious appetite for data.

Energy and food production

By placing things such as these data centres with their vast arrays of servers but also greenhouses with their constant artificial lighting and heating within the belly of the mountain, waste heat from these activities can be used to heat apartments, hotels and offices on top of it. The mountain offers an opportunity for food production due to the enormous amount of square meters it creates for urban farming. With efficient energy use, smart LED lighting and hydroponic systems, the large energy demand of this type of production can be arranged for in a much more environmentally sound manner.

Team

Concept

Rotterdamse Dromers | Derek van den Berg, Rodney Kastelan en Stijn van Pelt

Parametric modelling, structural design

Summum Engineering | Diederik Veenendaal

Acknowledgements

VORM

Services: Parametric modelling, structural design